News detail

Main factors affecting the quality of castable precast components

The quality of refractory castable precast components is inextricably linked to the manufacturing process. The manufacturing process significantly affects the microstructure and uniformity of the material. For example, insufficient vibration time during the vibration molding process of ceramics or refractory materials can prevent air bubbles from escaping smoothly, leading to increased porosity. It can also result in uneven vibration of the slurry, causing numerous surface defects, all of which are sources of crack initiation and propagation. Furthermore, in manufacturing a batch of materials, an immature manufacturing process can lead to variations in material quality. In erosion wear testing, when studying the erosion wear mechanism of a material, multiple samples exhibiting different properties can affect the test results and even lead to misleading conclusions.

Curing Procedures

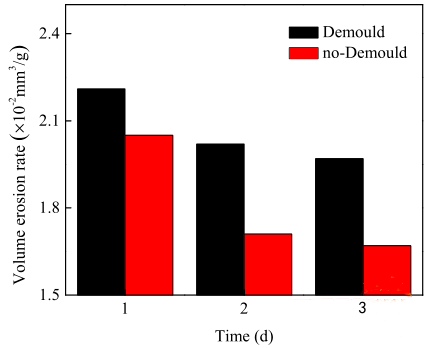

Similar to on-site construction, even in the laboratory, the castable precast components require curing. Since this experiment used cement-bonded castables, improving the bonding strength between cement, aggregates, and fine powder is crucial. Curing time and methods will be discussed in turn. The hardening of castable precast components is closely related to ambient humidity. The preparation and curing processes in this experiment were conducted under laboratory conditions, which may not necessarily reflect on-site construction conditions. All demolded samples were dried at 110℃ for 24 hours. Figure 1 shows the relationship between curing time (1 day, 2 days, 3 days), curing method (demolded, not demolded), and volumetric wear rate.

Several conclusions can be drawn from Figure 1:

(1) The volumetric wear rate decreases with increasing curing time, indicating that longer curing time has a better effect on the wear resistance of castable precast parts. However, the requirements are basically met after two days of curing without demolding. Although the wear rate will decrease further with increasing time, the impact is limited.

(2) Curing without demolding is significantly better than curing with demolding. The wear resistance of castable precast parts cured without demolding is generally better.

Curing refers to the dehydration process of castable precast parts. The amount of water added is also related to the curing time. During demolding curing, the precast parts have a wider contact range with the surrounding air, and the moisture evaporates faster during the curing process, which is not conducive to the cement generating higher strength. During the experiment, it was found that the mass of different castable precast parts will change to different degrees during the curing process. For example, the mass is generally smaller when cured in air. The high cement content in the precast parts makes the material more dense and has better wear resistance during the hydration process. During the curing process, try to keep the moisture in the castable precast parts, and you can water the surface appropriately.

Water Addition Amount

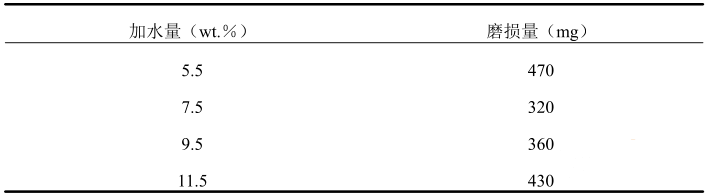

The amount of water added varies depending on the environment. Taking the construction process of castable refractory as an example, too little water will lead to poor fluidity and difficulty in casting, while too much water will affect the strength of the castable refractory after molding. An appropriate amount needs to be added. In a laboratory environment, experiments were conducted to determine the optimal water addition amount. When the water addition was less than 5%, the fluidity was very poor, the large aggregates were highly exposed, and the surface porosity was high. Therefore, the minimum water addition was set at 5%. Table 1 shows the relationship between water addition and volumetric wear rate. It can be found that a water addition of around 7.5% results in the optimal state for castable precast parts.

Erosion

The erosion test was conducted under the following conditions: erosion time of 20 minutes, erosion angle of 45°, and abrasive velocity of 10.8 m/s.

During the test, it was also found that differences in raw materials have a significant impact on castable preforms. For example, the high-alumina bauxite clinker used varies depending on its origin and firing process, with human factors having an even greater influence. Castables made from different bauxite clinker may exhibit excellent wear resistance in some areas and poor wear resistance in others, resulting in poor uniformity of the castable preforms. Therefore, the test samples should ideally be from the same manufacturer and batch, or higher-quality, more uniform high-alumina homogeneous material should be used.

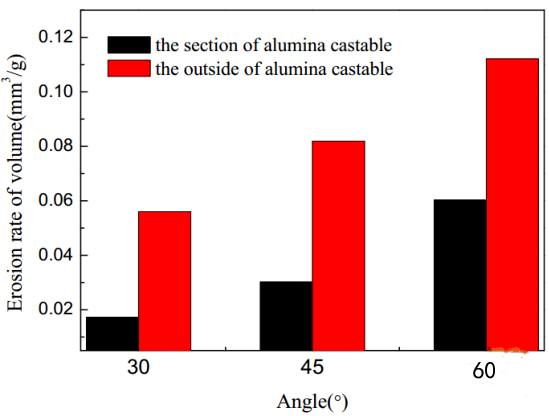

Figure 2 shows the volumetric erosion rate test results of the original formed surface and internal cut surface of the high-alumina castable preform after testing at erosion angles of 30°, 45°, and 60°. At erosion angles of 30°, 45°, and 60°, the volumetric wear rates of the original formed surface and internal cut surface of the high-alumina castable preform are 0.056 mm³/g and 0.017 mm³/g, 0.082 mm³/g and 0.030 mm³/g, and 0.112 mm³/g and 0.060 mm³/g, respectively. Their volumetric wear rates all increase with increasing erosion rate, and the volumetric wear rate of the internal cut surface is lower than that of the original formed surface.

High-alumina castable precast components are brittle materials, exhibiting the mechanical characteristics of brittle materials: high hardness, high brittleness, and relatively high compressive strength. During erosion, they also exhibit the typical erosion wear behavior of brittle materials. At small erosion angles (around 30°), the main erosion wear mechanisms are cutting and plowing actions. However, at heights of 90°, the erosion wear mechanism primarily involves crack formation and propagation caused by brittle fracture.

For this type of “aggregate-matrix” refractory material, the eroded surface is often enriched with a matrix that has low hardness and relatively low strength. Therefore, cutting at small angles often only erodes the matrix to a certain extent. As the erosion of the matrix gradually completes, or even before it is complete, the aggregate begins to be exposed. However, the destructive effect of cutting on high-strength, high-hardness aggregates is very limited; mostly, collision occurs. Furthermore, the increased proportion of aggregate creates stress concentration zones that resist erosion wear. Due to the obstruction of the aggregate, abrasive particles find it difficult to further erode the material. Therefore, the volumetric erosion rate of high-alumina castables is not high during small-angle erosion.

This can also be analyzed from an energy perspective. During small-angle erosion, the reverse erosion stress of the target material is relatively small, resulting in a smaller actual stress converted into material volume loss, thus leading to a low volumetric wear rate. As the erosion angle increases, brittle fracture gradually replaces cutting and plowing actions as the main cause of material erosion wear. At high erosion angles, the aggregate portion of high-alumina castable precast components becomes the primary carrier resisting erosion wear. As erosion time increases, cracks gradually develop in the aggregate, leading to crack propagation and eventually the detachment of large aggregate particles, resulting in significant volume loss of the target material and a high erosion wear rate. According to typical erosion theory for brittle materials, the maximum erosion rate occurs at an erosion angle of 90°.

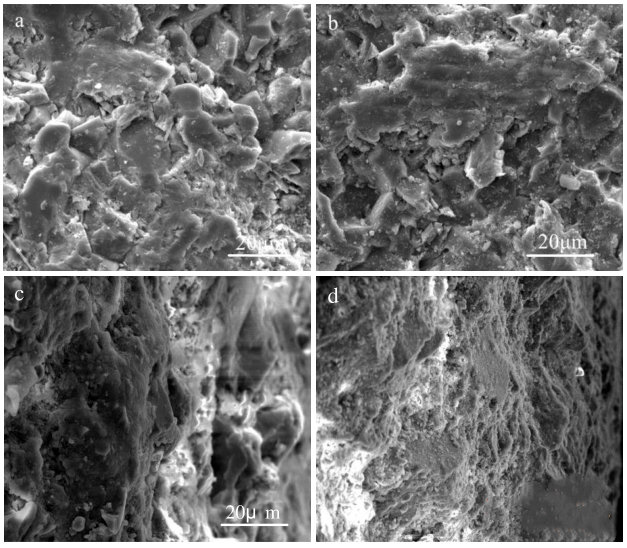

As shown in Figures 3(a) and (c), for the original formed surface of the high-alumina castable preform, under the condition of 4 minutes of erosion time, the abrasive erosion damages only the matrix and fine powder of the aggregate covering the target surface. The aggregate is only initially exposed, with intact morphology, and there is basically no crack generation or propagation. Although in some places the aggregate has acted as a barrier against erosion, the matrix is still a stress concentration point. Observation of Figures (b) and (d) shows that for the internal cross-section of the high-alumina castable preform, the abrasive erosion wear is mainly resisted by large aggregate particles, while the matrix and fine powder fill the gaps between the aggregate particles, thus providing protection. However, the erosion time is relatively short, and the erosion angle is not the maximum 90°, so the generation and propagation of cracks are not obvious. However, the stress at this stage is basically borne by the aggregate with higher strength and better wear resistance, so the volumetric erosion rate of the material is not large. By comparing the longitudinal sections (a) and (c), it can be seen that when the erosion angle is 30°, only a small portion of the aggregate is exposed, and the morphology is intact without cracks. The matrix part on the original forming surface of the material is not even completely eroded. The main damage mode is cutting, but the cutting effect of abrasive particles on the aggregate is not obvious. Until the erosion angle is 60°, the degree of aggregate exposure increases further. A few parts of the aggregate are basically completely exposed, and the exposed parts and the matrix part are evenly distributed. Some aggregates are exposed with sharp corners to resist the erosion and wear of abrasive particles, becoming the main places to bear erosion. However, overall, it is still in the morphological structure of the aggregate wrapped by the matrix, and the erosion and wear mechanism is still mainly cutting.

Send inquiry

Please Leave your message you want to know! We will respond to your inquiry within 24 hours!